- John Belden

- Reading Time: 6 minutes

With the advent of digital technologies, hybrid cloud solutions, and the evolution of ERP implementation models that demand higher levels of participation from the software vendors, the necessity to put in place high-performing multi-vendor teams is becoming more common. Program leaders are having to increasingly deal with vendors that have misaligned incentive plans or are looking to target each other’s project territory.

One model to minimize the issues associated with the multi-vendor environment is to effectively hand the entire problem to one system integrator. In this model, the client places the full burden of sourcing and contracting with the systems integrator. Clients will typically pay anywhere from a 10-20% premium for this arrangement over and above what they would have paid to develop a DIY model. The downsides of this approach (besides the cost uplift penalty) include vendor lock-in, making it nearly impossible to shift vendors once the program has started, and the potential loss of agility to shift directions and approach if the SI has established a vendor relationship that lacks flexibility.

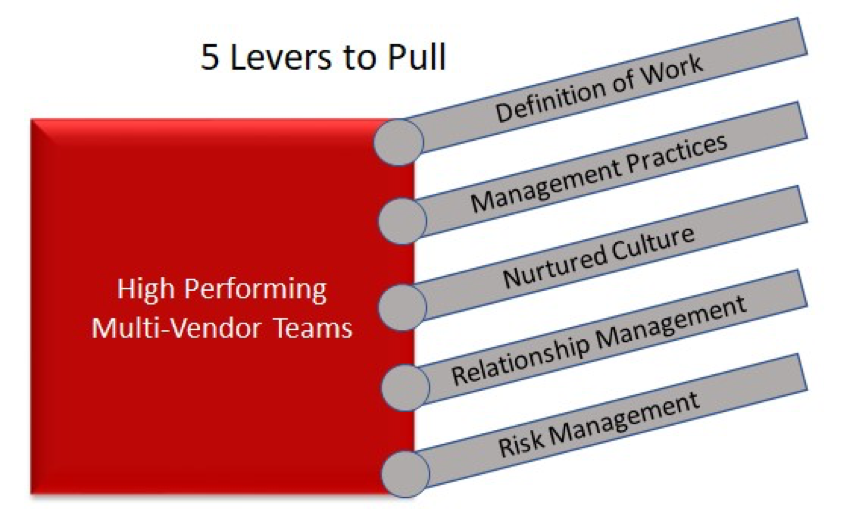

For those transformation leaders that are more inclined to maintain control of their own destiny and keep that 20% premium as dry powder to address contingency and enable additional capabilities, there are five levers to put in place to sustain a high-performing multi-vendor team.

Lever 1 — A Clear Definition of Work

To get started on the right foot, there needs to be one common definition of work and responsibilities that is shared with all parties. There are several essential definitional elements that can be used to enable each vendor to share a common view of the world. These include:

- The basic business case. What is the purpose of the program and what corporate performance metrics are expected to be changed? Providing each vendor with a clear understanding of the business case will enable them to make decisions that, with increasing probability, will be aligned with the overall best interest of the client.

- A clear and complete description of the scope of work and the environmental factors that contribute to any estimate, as examples: software platforms, business process inventories and backlogs.

- A unified methodology for the program that clearly outlines all deliverables that are attributed to all parties in the program.

- A common RACI which outlines which vendor has responsibility for each major activity, deliverable, or key decision.

- A dependency matrix that illustrates where vendors are dependent on each other’s performance to successfully complete their own individual scope of work. This dependency matrix may also be used to reflect service levels required from each vendor’s performance to enable the network of vendors to be engaged in the program.

These five definitional elements should be captured in controlled documents and referenced in each vendor’s contract. In the case of SAP S/4 implementations, SI’s and SAP should be compelled to provide a joint proposal that clearly outlines the responsibilities of each party in order to complete a successful implementation. In the case of a digital transformation program, the SI can be contracted to establish a baseline set of information in a Phase 0 or road-mapping engagement. These elements then become the foundation of individual RFP’s that can then be modeled to align with specific sourcing objectives.

Lever 2 – Management Practices

Once all parties have agreed on the work and responsibilities, all vendor stakeholders need to agree or be instructed on how the work will be managed. We can break these program management activities into three broad categories:

- How the program will be planned — This involves the development of staffing models, integrated project plans, and shared milestones. It also must include clearly defined phase or milestone exit criteria with elements of responsibility that are clearly understood as an essential component of developing a workable plan.

- Status and reporting RAID (Risks, Actions, Issues, and Decision Management) administration — A harmonized process for status reporting that requires all vendors to report information in a consistent and complete fashion is vital.

- High-performing multi-vendor programs will adopt shared RAID logs and resolution plans, however, these RAID logs will require special protocols for the treatment of vendor-specific RAID entries to discourage the possibility of vendor mischief.

Transparency of reporting to the program PMO and the controlled availability of information to all vendors is something that needs to be carefully managed. While transparency is often viewed as a good thing and an enabler, it is easy to conceive how one vendor may use the problems of another vendor to provide cover for flaws in their own delivery.

Lever 3 — Nurturing Culture

Culture is something that is often viewed as soft and is derived primarily from the senior leadership of the program. However, there are a few cultural points that can challenge program teams early if they are not proactively addressed. These include:

- Methods of collaboration – Teams will need to adopt standards for use of collaboration technologies. Tools such as Teams, Skype, WebEx, etc., can become a real headache if all parties are not able to use in a secure fashion.

- Knowledge management and intellectual property – Vendors and clients will need to develop specific internal controls on how a vendor’s proprietary assets and intellectual property will be managed and deployed at the client’s sites to ensure the appropriate protections.

- Communications – All firms need to agree on what information will be communicated at a program level to all vendors. What also needs to be agreed upon is how each firm will communicate with their own staff and who has the authority to call meetings that involve team members from other firms.

- Senior team role modeling – Most cultures evolve based on the behaviors and actions of their leadership teams. Client leadership teams would be wise to hold vendor leadership meetings in the line of sight of the project team to help establish the culture. Also necessary will be for the vendor leadership to be consistent in communicating to their assigned teams their personnel expectations regarding collaborations so there is no mistaking what is expected.

When contracting vendors in this model, it is important to specifically address and resolve the first two points in this section to efficiently enable a high performing team.

Lever 4 -Vendor Relations

Vendor relations are typically never better than the day you sign the deal. When working with multiple vendors, an increased level of attention is required to ensure that all parties are working together as planned. For the vendor management teams this involves:

- Contracting – Clients and vendors will need to address the following three provisions:

- Estimating methods and transparency — It is important to understand how a vendor estimate may be impacted on other vendor’s performance.

- Responsibilities and accountabilities for enabling client’s other third parties – Look back on the vendor dependency matrix identified as part of defining the work.

- A specific link for the vendor to acknowledge their responsibilities for reporting and managing that are aligned with the program’s management.

- Performance monitoring – All vendors will need to be required to report on their own individual performance with regard to their responsibilities. In addition, vendors should be required to report on the specific performance of other vendors if the vendor’s performance is highly dependent on another third party.

- Vendor management meetings – Ongoing regular meetings with the vendor management office are required.

Lever 5 – Multi-Vendor Risk Management

There are several new risk points that surface and require special attention in the multi-vendor model. These risks include:

- Under-investing in enabling the multi-vendor model — Companies that don’t recognize the level of initial investment required to set up these models are likely to assemble them such that they are doomed to fail.

- Lack of organizational discipline – Once established, these multi-vendor models require continuous tending. Failure to manage vendor relationships or enforce reporting standards often results in the overall erosion of anticipated benefits.

- Unbalanced risk profile – It is not uncommon for the most vocal of vendors with the most dominant project profile to amplify their own risks on a program risk matrix.

These risks should be added to every multi-vendor risk profile for proper evaluation.

As with any well-established risk management program, risks need to be monitored. PMO’s can monitor the overall potential for elevated risks by examining the RAID logs, monitoring the quality and consistency of performance at vendor hand-off points, and properly capture any specific issues that were raised during the vendor relations meetings.

Getting Started

There can be a significant pay-off for clients who enable a multi-vendor model to support their transformational programs. However, companies need to be prepared to put forward the effort required to enable the capturing of program benefits. There is a reason that the SI will typically look for an uplift of 10-20% to serve as a general contractor for a program, and it is not simply to make additional profit.

To get started on the right foot, transformation program leaders need to develop a comprehensive sourcing strategy in collaboration with their procurement and IT teams. Engaging a sourcing advisor with plenty of experience in establishing these types of models wouldn’t be a bad idea, either.

Comment below, follow me on Twitter @jmbelden98 find my other UpperEdge blogs and follow UpperEdge on Twitter and LinkedIn. Learn more about our Project Execution Advisory Services.

Related Posts

Related Blogs

5 Red Flags That Reveal Your RFP Is Weak and Why Vendors Know It Before You Do

Understanding Systems Integrator Behavior: Tier 1 vs Tier 2

What is Phase 0 and Why is it Potentially Your Most Important Project Phase?

About the Author